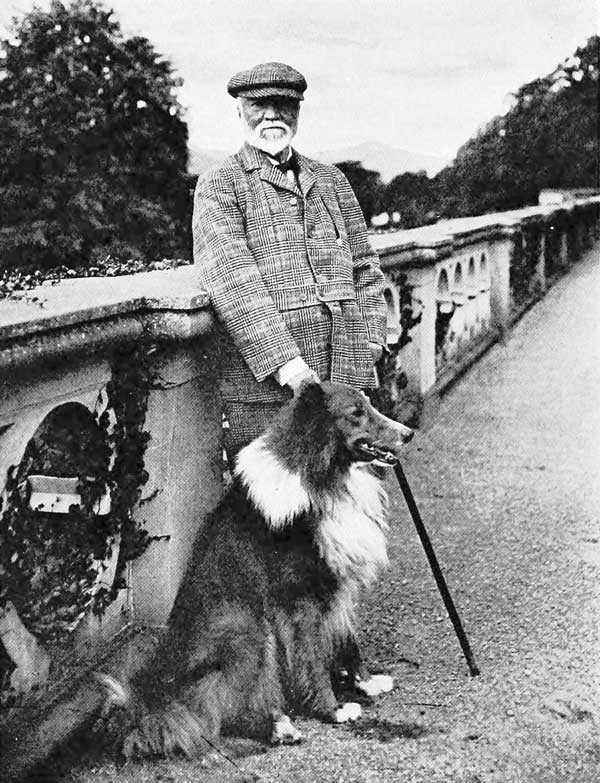

Andrew Carnegie's legacy

The “richest man in the world” at the turn of the century, Scottish-born American industrialist Andrew Carnegie purchased his beloved Skibo castle in 1898 and turned it into one of the finest private residences of its time. Considered the father of modern philanthropy, he gave grants to create 2509 free public libraries around the world, with three of them in the Creich Parish.

By Silvia Muras

Born in 1835 in a weaver’s cottage in Dunfermline, along with his parents and younger brother he emigrated to Allegheny, Pennsylvania, United States, in 1848 for the prospect of a better life. He started working as a bobbin boy in a cotton mill at age 13, then as a messenger for a local telegraph company, where he was promoted to telegraph operator. He was a voracious reader. A retired merchant, Colonel Anderson, loaned books from his small library to local boys, including Carnegie, with books providing most of Andrew Carnegie’s education throughout the years.

He became the private secretary of Thomas A. Scott, and at age 24 he succeeded him as superintendent of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Carnegie’s first investment came when Scott alerted Carnegie to the impending sale of ten shares in the Adams Express Company at $60 a share. His mother raised $500 by mortgaging their home, while Scott lent him the remaining $100, and soon the dividends began rolling in.

By age 30, Carnegie had amassed business interests in iron works, steamers on the Great Lakes, railroads, and oil wells. He was subsequently involved in steel production, and built the Carnegie Steel Corporation.

Philanthropy

In 1868 Carnegie wrote himself a letter outlining his plans for the future. He was determined to resign from business at age 35 and live on an income of $50,000 per year. In his autobiography, Carnegie remembered that, as a child, “I resolved, if wealth ever came to me, that it should be used to establish free libraries.” He started giving grants for libraries, making the adoption of the Public Libraries Act a requirement to access his donations. Known as the ‘Carnegie formula’, town councils had to demonstrate there was a public need for a library, that they could provide a suitable site and that they could maintain, furnish and stock them. The first of his free libraries opened in Dunfermline in 1883.

In his 1889 essay The Gospel of Wealth he wrote: “The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced”

In 1901 Andrew Carnegie sold his steel company to J.P. Morgan for $480 million. This sum was 2.1% of the US GDP, which would translate today to near $400bn. At this point he retired from business completely and concentrated in distributing his fortune in earnest, giving away over $350 million in his lifetime.

In 1887 Andrew Carnegie married Louise Whitfield. She was fully supportive of his charitable endeavours, having signed a prenuptial agreement giving up her rights to her husband’s estate in return for an annual income of $20,000.

The couple came to Scotland to lay the foundation stone of the Edinburgh Carnegie Free Library, his gift to the city. Angus Macpherson recounts that it was at that ceremony that Mrs Carnegie fell in love with the music of the pipes. They hired his brother John Macpherson as piper for Kilgraston House, the Carnegies’ first Scottish home, and in 1888 they rented Cluny Castle where they spent the next ten seasons entertaining guests.

Skibo Castle

In 1897 the owner of Cluny Castle, Cluny Macpherson, got married and they had to look for a new suitable Scottish home. Their requirements were “a private anchorage for his luxury yacht the Sea Breeze, a trout stream and a waterfall”. They soon found Skibo Castle and estate, which they purchased for £85,000 the following year. The estate had nearly 20,000 acres and 200 tenants.

They extended and renovated the castle with great luxury. Mrs Carnegie with their daughter Margaret (aged 2) starred in the ceremony of laying the foundation stone of the new extension which was going to dwarf the original building. The castle had a state of the art 25ft long indoor heated swimming pool, and was the first building in Scotland to have an Otis lift. Electric lights and hot and cold running water were standard in its 20 guest rooms. Such was Skibo’s reputation that in 1902, King Edward VII unexpectedly paid a visit to examine the latest in luxury as he contemplated the refurbishment of Buckingham Palace.

“Heaven itself,” Carnegie declared, “is not so beautiful as Skibo.”

The family arrived in May and stayed until September. The annual return of Mr & Mrs Carnegie to the area was celebrated with great fanfare, decorating the streets of Ardgay and Bonar with bunting and folliage. In May 1899, a welcoming committee representing Spinningdale, Achary, Clashmore, Evelix and Astle presented Carnegie with the famous silk flag bearing the Union Jack on one side and the Stars and Stripes of the United States on the other side.

The family continued to entertain many important guests: Rudyard Kipling, Matthew Arnold, Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Lloyd George, Woodrow Wilson, Theodore Roosevelt, William Gladstone, Herbert Spencer, Helen Keller, Herbert Asquith, Booker T. Washington... and many others.

At Skibo, Andrew Carnegie ran his business enterprises with one hand while he courted the literary and creative world with the other. A steady flow of cables and correspondence was received, with postman David Ross, originally walking daily from Ardgay Post Office to Skibo Castle with Andrew Carnegie’s mail!

Andrew Carnegie enjoyed fishing and playing ‘Dr Golf’, as he called it. The grouse and deer were left to their guests, as he didn’t take part in any shooting. He didn’t like smoking either, and no one but a duke or a king dared to light a cigarette inside Skibo Castle. Angus Macpherson, who became his piper in 1898, used to wake up guests playing at 7:45 am sharp, and organ music was played each morning during breakfast.

William Thomson, great grandson of Andrew Carnegie, recounts that in 1899 Rudyard Kipling stayed at the Old Manse in Creich together with his father and the artist Philip Burne-Jones. On the 21st August, Burne-Jones sent a letter to Andrew Carnegie at Skibo including an ink sketch depicting the three men mourning their last bottle of whisky. Carnegie sent the men a case from the castle’s cellars and he received another sketch celebrating the whisky. He was amused by the whole story and had the sketches framed.

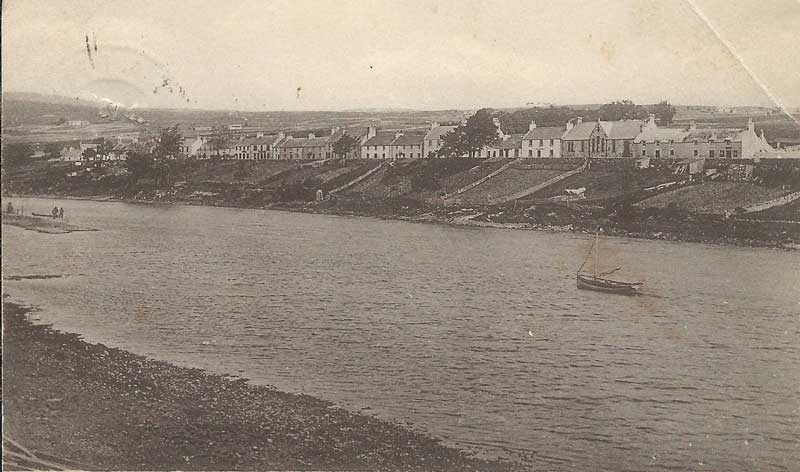

(Left) Bonar Bridge West End before the library was built. The site cost £150 and it was purchased from Colonel Mackintosh (Sutherland Highland Rifle Volunteers). (Right) Unfinished library with the windows still to be fitted. © Donald Brown

Local libraries

In 1900 Mr & Mrs Carnegie pledged £1,000 towards a library in Bonar Bridge, £250 for a library in Spinningdale, and £250 for a village hall and library in Rosehall. A commitee of 20 members representing the three libraries was formed, chaired by Dr Macrae of Bonar Bridge.

The first to open was Spinningdale Library, in October 1900. The architects were Andrew Maitland & Sons, Tain with works carried out by local tradesmen. The librarian was Duncan Campbell, Larachan.

A suitable plot for the library in Bonar Bridge was found on the west end of the village and purchased for £150 from the Sutherland Highland Rifle Volunteers. Works commenced in the summer of 1900, with the official opening held in October 1901. The appointed contractors were: Builders, William Macpherson, Bonar Bridge and Grant Brothers, Inverness; Joiners, Nicol & Son, Tain; Plumbers, Mackenzie & Co, Invernes; Slater: A. C. Fraser, Inverness; Painter, Archibald Cameron, Bonar Bridge; Plasterer, Robert Ross, Spinningdale. The Architect was Mr J. Pond Macdonald, Inverness.

On the front of the building, there are two inscriptions, in English and Gaelic, of a quote from Carlyle: “All that mankind has done, thought, gained or been, it is lying, as in magic preservation, in the pages of books.” There were concerns with the accuracy of the Gaelic text, with a press article of December 1901 asking readers to suggest a better translation.

The survey made in 1903 stated that the library had 600 volumes, the daily average attendance was 55, with 198 ticket-holders, and a total lending of 2,443. The librarian was John M. MacDonald. Carnegie continued donating £100 annually towards books and by 1906, there were 1,000 volumes on the shelves. Over the years, this building has also acommodated a GP surgery and The Highland Council offices. Today, it is still a library operated by HighLife Highland, and very much at the centre of the village’s life.

The Rosehall Library took longer to build, partly because of difficulty finding a suitable place. The plot for Rosehall Library was finally kindly provided by W. E. Gilmour in 1902 and the library and hall opened in August 1903, with a large ceremony presided by W. E. Gilmour and attended by Mr & Mrs Carnegie, who donated a further £50 towards books. It was used as village hall until a new hall was built next door in 1938.

Andrew Carnegie’s buildings trail

Skibo Castle

Originaly a viking stronghold, it was the residence of the bishops of Caithness in the 1200s. Bought in 1898 by Andrew Carnegie, who made extensive renovations. It is now operated as The Carnegie Club, a members-only residential club, offering members and their guests accommodation, a private links golf course and a range of activities including clay pigeon shooting, tennis and horse riding.

Aultnagar Lodge

Built in 1910 as a private retreat so that Andrew Carnegie and his family could escape the hustle and bustle of Skibo Castle. At only 12 miles from Skibo, it had Falls of Shin at the bottom of its garden. Today it is operated as a hotel, featuring, among other traces of Andrew Carnegie's era, the only complete Liberty of London interior in Scotland.

Clashmore Hall & Library

Erected in 1907 for the Skibo Castle Estate workers and the residents of Clashmore. It was built in the same stone as Skibo, featuring a pipe organ on one end, pitch pine finishings and a hot water heating system.

Bonar Bridge Library

Designed by John Pond Macdonald from Inverness, it was built in yellow sandstone at a cost of £1,116 of which £1,070 came from Andrew Carnegie. It opened to the public on the 2nd January 1902.

Spinningdale Library

Purpose built village hall and reading room erected in 1900 with a £250 grant. Today a private residence.

Rosehall Hall & Library

Village hall and reading room built at a cost of £350, and it opened in 1903. It was sold as private residence in 1973.

Tain Library

The Tain Carnegie Free Library was officially opened in August 1904. The architects were A. Maitland and Sons, and it costed £1,250.

Dornoch Library

Opened in October 1907. The town council had been given an initial grant of £1,250, however, the money fell short for the project and Mr Carnegie gifted an extra £304 to complete the building.