Lichen safari

Cherry Alexander tells us about the recent Lichen Safari in Ledmore & Migdale Woods. These complex organisms are made up of a fungus and one or more algae living together.

By Cherry Alexander

The first Lichen Safari was rained off and although the Easter Ross Ranger, Marcia Rae from High Life Highland, kept us well informed, not everyone booked on the first one could make the re-booked date, so there were only five of us. We met at the Torroy car park, below the log cabin in the Fairy Glen, part of the Woodland Trust’s extensive reserve at Ledmore and Migdale woods, extending to 690 Hectares or 1,707 acres: one of the largest sites owned by the Woodland Trust.

Before we left the car park Marcia lent us hand-lenses, an essential for looking at the fine detail of lichen. Lichens are complex organisms, made up of a fungus and one or more algae living together. The fungus provides the body, or thallus, in which the algae live and the algae contribute by producing essential nutrients for the fungus by photosynthesis. She explained that as the subject was extensive and complicated, she would try and explain to us the main subdivisions of lichen, and show us some local examples.

They fall into 3 groups:

- Crustose, these are crusty lichens which cannot be easily removed from the bark of the tree with a fingernail.

- Foliose, these leafy lichens can be lifted from the tree or ground with a fingernail and often have root like hairs on the underside.

- Fruiticose, branched lichen attached to the host at only one point.

Because our subjects are diminutive and widespread in our clean air, we didn’t have to walk far before we found the first example, a foliose lichen growing amongst the gravel. Heather and Marcia were down on the ground to take a closer look. We walked on a little to a stand of birches, where Marcia picked up a fallen twig and showed us some of the lichens that grow locally on birch, and on a lot of other things too. These included a puffy looking Hypogymnia, which is foliose, and a fruiticose Usnea subfloridana, which is the UK’s commonest lichen and is also very tolerant of air pollution, not that it has to worry about that up here in the Highlands.

© B&C Alexander/Arcticphoto

Our next stop was to check the walls up at the log cabin, which were rather dry, but growing on the top were lots of spiky strands of Cladonia, in the same family as Reindeer Lichen. I had purchased some laminated identification cards to assist me, but was disappointed to find that there were no common names listed. A quick Google search previous to the meet and I had found a spread sheet with 800 plus common names for lichens found in the UK. There are the Pepperpot Lichen and Handwriting Lichen to mention just a couple.

Further along the track we found a stand of Rowan and their smooth bark was home to some fine examples of Crustose lichens, all sitting close against the bark, some of them had fruiting bodies on them for reproduction. Lichen have 2 ways to reproduce, either by spores, which are formed in the fungal part of the partnership, but in order to grow, these spores need to find the right algal partner. Some lichens reproduce asexually from propagules, containing both fungal and algal properties so they can quickly form another lichen if they land in the right place. But as these spores or propagules blow around in the wind, to be successful they need to land somewhere that offers conditions perfect to support them.

It was a fascinating afternoon, with a great deal to take in, so I am looking forward to the Lichen Safari that is planned in our own Gearrchoille Community Woodland for some time in October. It will offer a chance to come to grips with the wealth of lichen that live on our oak trees.

Lichens and wool

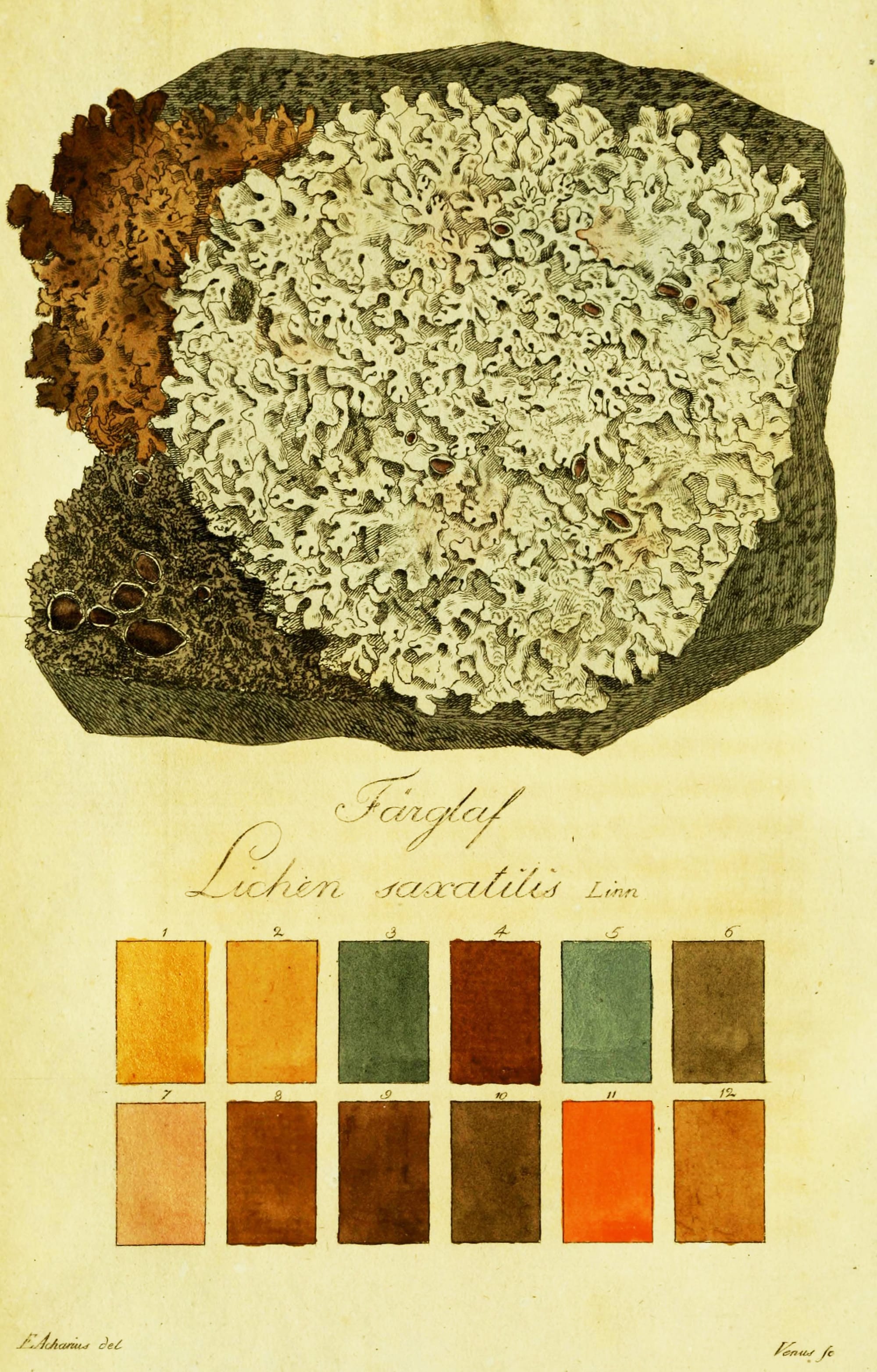

In the past, lichens played an important role in the Scottish economy. They were used for dyeing, both on a domestic scale and to supply manufacturers such as Harris Tweed. Its famous bright orange colour was obtained from a rock dwelling lichen called crotal (Xanthoria parietina). Traditionally, islanders used a spoon to scrap this greenish-grey lichen, and three-legged iron pots to boil it to obtain yellow, orange, or brown colours, depending on how long the wool was boiled.

Another lichen, Cudbear or Orchil (Ochrolechia tartarea) was harvested to produce a coveted purple and red. The name comes from Cuthbert Gordon, a chemist who patented the process to obtain the dye. At its peak, the factory in Glasgow processed up to 250 tons of lichen per year, more than what Scotland could produce. Eventually, Cudbear was overtaken by Turkey red and others, and the factory closed in 1851. Today, many tartan collections are inspired by the colours of Scottish lichens.