The Culrain Clearance riots

In 1820 the people on the estate of Culrain took direct action against the prospect of being cleared. The events constituted classic anti-clearance riots, the whole episode being described by the historian Eric Richards as an “explosion of physical resistance”.

By Malcolm Bangor-Jones

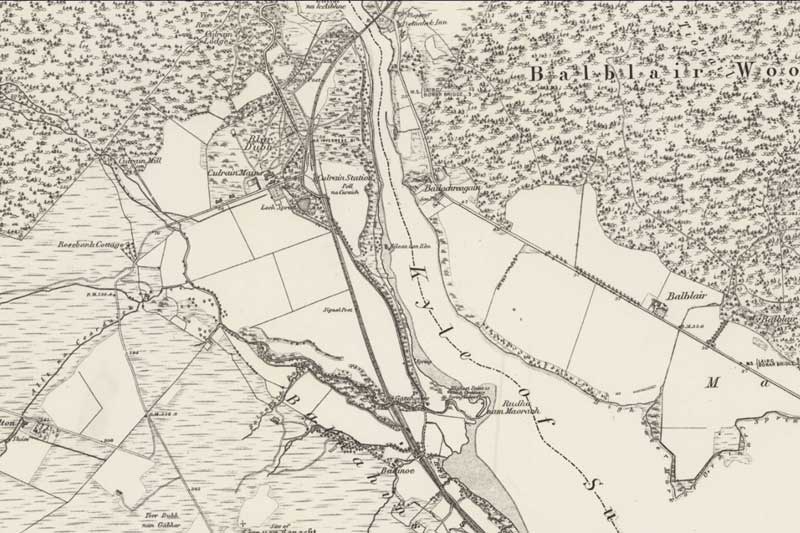

The Culrain estate stretched along the Kyle of Sutherland from Balinoe at its eastern end to Ochtow on the west where it bounded with the property of Ross of Balnagown. It had formerly been known as Carbisdale but had been renamed by the Munros who owned Culrain in the parish of Rosskeen. In 1820 the Culrain estate was owned by Hugh Andrew Johnstone Munro of Novar – a young man who was a close friend of Turner and was to become known as an art collector.

The estate was managed by Novar’s factor Peter Brown of Linkwood who had a reputation as “one of the most skilled men in the North”. The whole estate had been let to a Major Forbes – this was Donald Forbes, one of the leading tacksmen on the Reay estate where he was tenant of the large sheepfarm of Melness.

A good deal of the Culrain estate - it is not yet entirely clear how much – was to be devoted to a sheepfarm. This would require the removal of 60 tenants who, according to Novar, had rejected his proposals to provide for them. Some of these tenants, it would appear, had resettled on the estate after being cleared from Sutherland.

The necessary legal papers were obtained from Tain sheriff court and James Stewart, a sheriff officer, was entrusted with serving them on the tenants. He was accompanied by the required two witnesses, William Munro and Andrew Tallach from Morangie. When Stewart heard that the people intended to offer resistance, he took Andrew Ross, a constable from Tain, along with his witnesses.

Unfortunately for Stewart, Ross let slip the reason for their visit. When, on the morning of 1 February Stewart left the Culrain dram shop where his witnesses had slept, he was surrounded by a mob of about 150 “furious women”, armed with sticks or batons, who seized him and took the summonses from his pockets. Stewart and his witnesses were driven off.

The sheriff officer had come to serve what have been referred to as ‘letters of removal’. This does not mean that the people were to be evicted there and then. The papers were in fact summons of removal citing the tenants to appear at Tain sheriff court. In the event of them being unable to offer any defence (for instance, possession of a current lease) they would have been decerned to remove at the term of Whitsunday towards the end of May (by law tenants had to be warned to remove 40 days before the term). Actual eviction was a separate step with its own legal procedure which could follow if the tenants did not remove themselves.

Novar wanted troops being brought in to deal with the rioters. The sheriff, Donald MacLeod of Geanies, preferred to try and persuade the people to end their resistance. He even asked Thomas Dudgeon, who had been promoting the Sutherland & Transatlantic Friendly Association to assist cleared tenants on that estate, to help. This was all in vain for when Stewart returned to Culrain to serve criminal warrants he was again deforced by a mob of women.

The Lord Advocate refused the sheriff’s request for troops. MacLeod was therefore left to assemble a force comprising a party of constables and sheriff officers, a contingent of the Ross-shire militia, some soldiers, and various gentlemen. On 2 March, having reached the boundary of the estate, they were met by a mob of about 300 to 400 people, chiefly women but also young men and boys, who proceeded to throw stones. According to the sheriff there was a second line behind them of men, some or many of whom, had arms.

They were met by a mob of about 300 to 400 people, chiefly women but also young men and boys, who proceeded to throw stones

In the face of overwhelming odds, the sheriff’s force retreated back to Ardgay. However, this was not before some of the militiamen, contrary to MacLeod’s orders, fired as they were retreating. Two or three women were severely wounded, and one later died. This was Isobel Matheson, a “fine young woman of 17 years of age”, a daughter of Donald Matheson, the catechist in Culrain.

The Lord Advocate refused the sheriff’s request for 500 troops and three pieces of artillery and looked for Culrain to be settled as quietly as possible. Novar, much to the concern of fellow landowners, looked for a compromise. He persuaded Forbes to permit the tenants to remain as his subtenants in return for a reduction of rent. The people were, however, prevailed upon to accept the summonses.

The Sutherland factor at the time commented that Novar had indeed compromised the business with his rebellious tenantry and within the year the factor was claiming that the consequences of the “non punishment” of the Culrain rioters was being felt.

The minister of Kincardine, Alexander MacBean, played a central role in reaching such an accommodation. While MacBean may have been critical of the clearances, he clearly felt it was the tenants’ duty to submit to their landlord. MacBean was presumably accompanied by his catechist, who was said to have been “most assiduous in his endeavours to bring the people to submission to the laws.” There was to be a rather ill-natured public dispute played out in the newspapers between MacBean and the sheriff as to who had contributed most to bringing about peace.

Forbes remained responsible for the rents of the whole estate but was probably only allowed personal possession of part of Culrain itself and Ochtow. Unsurprisingly, Forbes brought an action for damages against Munro of Novar and later gave up his tenancy. He suffered during the period of low livestock prices during the 1820s and was sequestrated in 1827.

The events of 1820 did not represent the end of the people’s resistance to clearance. In 1840, Hugh MacIntyre, the tacksman of Culrain, brought summonses of removal against 20 subtenants. The sheriff officer was “violently deforced, and his life threatened should he again return.” However, the sheriff accompanied only by the parish minister went “among the disaffected People, and after much reasoning with them as to their Conduct & its results, the tenants at length desisted from all opposition, & did not molest the officer who again went forward & served the citations on them.”

However, on 19 March MacIntyre’s farm steading caught fire and 26 cattle were destroyed, as well as grain and farming implements. No perpetrators were discovered for what was suspected as an arson attack. Such attacks have been little studied in Scotland: the impression from newspapers is that such attacks were rare but not unknown in the north of Scotland.

MacIntyre later bought property near Tain which he renamed Culpleasant. His son, Peter MacIntyre, who was born at Culrain, farmed for many years at Findon, which he later bought, and was a member of the Crofter’s Commission.

The Culrain estate was bought in 1869 by a consortium of speculators headed by one George Grant Mackay who proceeded to sell it off in feus of from 20 to 5000 acres (from large crofts to small sporting estates). It was not without controversy: but that is another story.