The Gaelic of my youth

Uisdean Vass recounts how he started learning Gaelic. Growing up in Rosehall in the 1960s and 70s there was very little formal teaching, but Uisdean’s mum and dad –like many others whose parents had been fluent speakers– often used Gaelic idiom and words.

By Uisdean Vass

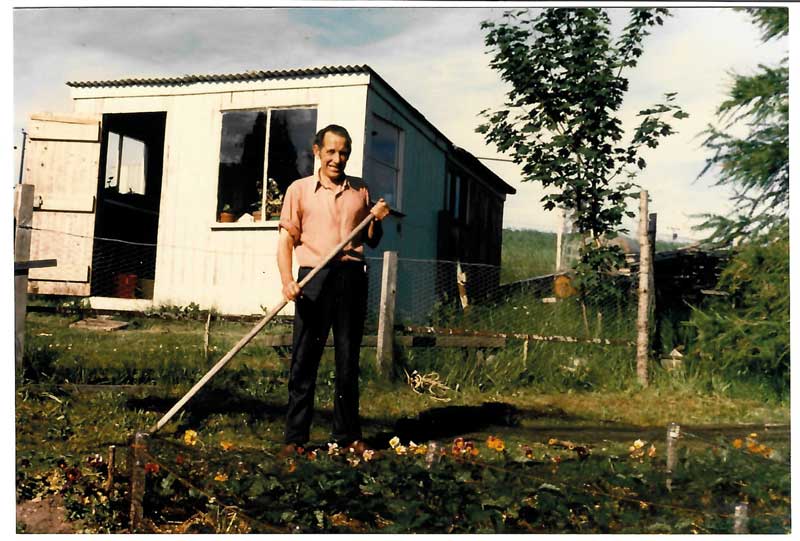

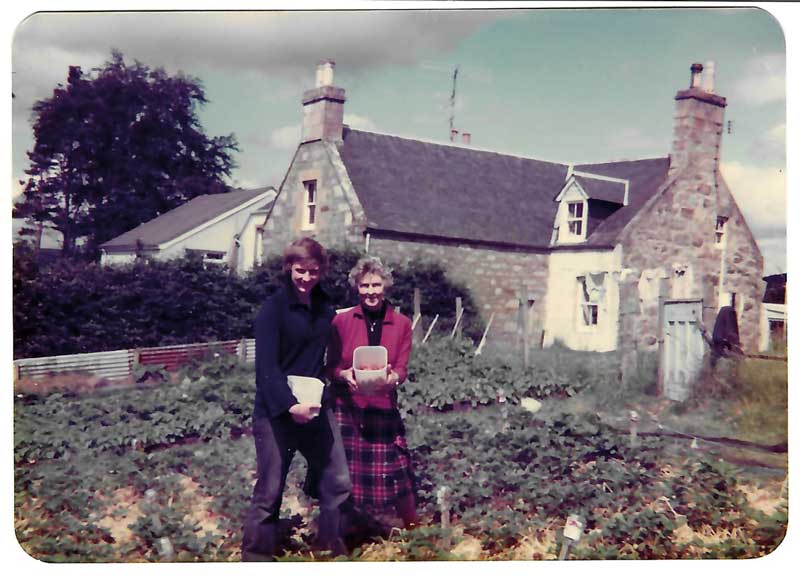

I was brought up in the Sutherland of the 1960s and 70s, living most of the time in Rosehall Schoolhouse. My mother, Joy Vass, was the Headmistress. My father, Andrew Vass was a fisher from Hilton, Ross-shire and his parents had been fluent in Gaelic. Joy’s grandparents, but not her parents, were also fluent. Neither of my parents were fluent in Gaelic, but they used Gaelic idiom in their English, and they also used Gaelic words directly in their English.

They used Gaelic idiom because their ascendants had learnt English from Gaelic. A few examples will suffice. We hear a knock at the door. Dad asks me “Who is it in?” meaning “Who is there?” This is straight from the Gaelic: “Cò (who) th’ (is) ann (in it)? Or another good example: “The hunger is on me” meaning “I am hungry”. Again this is straight from Gaelic: “Tha (is) an-t-acras (the hunger) orm” (on me). When my mother went to study in Edinburgh in 1938, she was teased by some of her Highland friends who were more recent English learners for the use of Gaelic idiom in her English.

What was more pronounced for me was Dad’s frequent use of Gaelic words and phrases in his English. I began to notice the use of the otherwise strange words when I was about nine or ten and I quizzed Dad about them, and he told me about their origin. Our talking about them caused him to remember more and I became very interested in the words and phrases and tried to write them down without any idea of how to spell them correctly. There may have been about one hundred or so words or phrases and this doesn’t sound a lot, but they did cover a lot of ordinary situations and we used them as a sort of code, which created a powerful bond between us. What was frustrating was that Dad couldn’t think about how to say something. He either knew it or he didn’t. Popular words and phrases often related to the weather such as “Tha fluich” (It is wet); “Tha fuar” (It is cold); “Tha stoirmeil” (It is stormy) “Tha sneachd ann” (It’s snowing ). Other words commonly used were “bodach” (old man); “cailleach” (old woman); “bradan” (salmon); “brochan” (porridge); ”corra-ghritheach” (herron), “spaideal” (smart - in the dressy sense) and many more. Sometimes he would say, “Tha mi deas a-nis!” (I am done for now! - can also mean I am ready now), or “Cuir e sinne!” (Put it there!)

Subsequently, when I started to learn Gaelic properly, I came across many of these words in their proper written form but some of the words Dad used are not in dictionaries and are unknown to the fluent speakers of today. These words and phrases may have come from the Seaboard Villages, meaning Hilton, Balintore and Shandwick. For example, I remember Dad warning me to avoid the “copach” (wasp’s nest”) in the garage but the dictionary says that “copach” means “frothy, foaming”. Another memorable word used by both Dad and Mam was pronounced “fya-oon” which I guess should be spelt “feann”. If you were feeling feann, it means that you are just a bit tired after a possibly long and difficult day, with a wee bit of a sniffle, feeling a little peckish and generally needing some care and attention including a hot Scotch broth by the fire and some fresh bread and butter! I still use the same word with my family (usually to good effect!) but there is no sign of it in the dictionaries.

I only picked up on some of the words quite recently. For example, Dad would often say to me something like this: “The jee-aching (challenge or problem) with Sandy Macleod [not a real person!] is that you never know how you will find him. He is bad for the droch nadar (evil temper)”. I only found out a few years ago that “jee-aching” was the word “deuchainn”.

I am very conscious of the terrible cultural loss suffered by my parents’ generation because they lost the language of their fathers

My father was also keen on some of the Gaelic proverbs, and for a child of the Great Depression one of his favourites as “Ith’s an-t-acras, Ith’s sam bith” (Eats the hunger, Eats the World”). Or as he would say, “The hunger will eat anything”. Another favourite was: “Is ceann mor air duine glic, is ceann circ air amadan”! This means “A big head on a wise man, a hen’s head on a fool”. He would then speak about the “ceann mor” of the Vasses!

There was no interest in formal teaching of Gaelic in 1970s Sutherland, but Gaelic choirs were very popular. It always seemed to me to be sad that people were singing beautiful words which they could not understand. There were no Gaelic speaking children in Rosehall Primary School the 1960s/70s and none, to my knowledge in Golspie High School during my time (1972 - 1978). I wanted to learn Gaelic so much that I rather neglected my French and Latin, seeing them only as ways of getting grades. This was a shame as you simply cannot go wrong learning languages. Mrs MacArthur, the Maths and RE teacher in Golspie, was fluent in Gaelic coming from the West Coast but she did not offer a class.

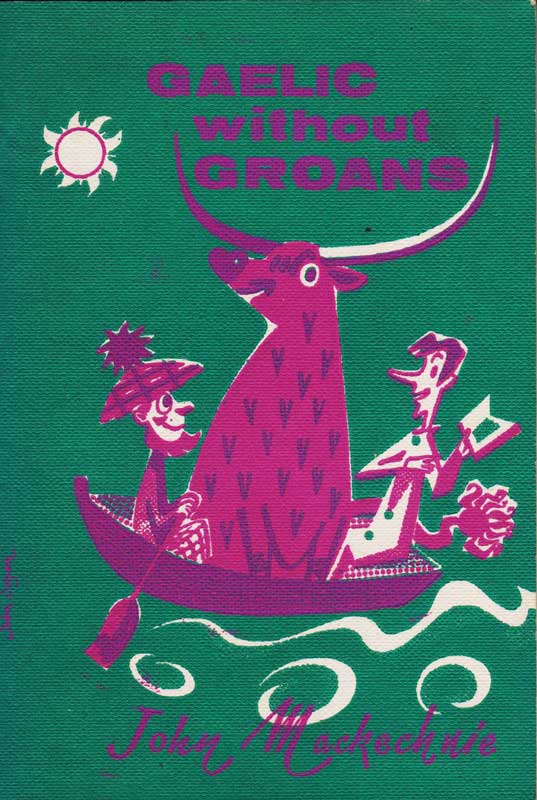

Neither was there much material for reading and learning. However, I got hold of a really good work by John MacKechnie called “Gaelic without Groans”. Though this book would now look to be long out-of-date, I can recommend it for the useful grammatical explanations. It helped me a lot, but my real problem was that I had no fluent Gaelic-speaking friend, and no reliable guide to correct pronunciation. I therefore tried to speak my halting Gaelic to anyone who might listen, whether they were a Free Church minister, and older crofter, or simply someone who had moved to Rosehall from the Islands. By the time I went to study in Edinburgh University in 1978, I had improved a little and I made friends with lads from the Western Isles, and they brought me on a lot. They had to be very patient! Many a fine chat we had after football or at ceilidhs.

Then I lost contact with fluent Gaelic speakers, and I am just picking up the language in later life. Now my son is showing an interest in Gaelic, after learning Spanish and Portuguese fluently, so I have taught him simple phrases for use in the house, such as “Mhatainn mhath Liam, bheil thu deiseil airson do chopan cofi?” (Good morning, Liam. Are you ready for your cup of coffee?) “Do chadal thu math?” (Did you sleep well?).

Why learn Gaelic in this day and age? The language is part of the great linguistic heritage of the Highlanders and indeed all of Scotland. I am very conscious of the terrible cultural loss suffered by my parents’ generation because they lost the language of their forefathers. There were no winners from this process, only losers. And language is endlessly fascinating; after all, it is a major distinguishing mark of our species. Gaelic, with its deep idiomatic speech and intricate verb and tense structure, tells us about the Celts. Demanding, frustrating, and beautiful as it may be, Gaelic is the beloved “song remembered in exile” as they say in Nova Scotia.